Why don’t Agile and management get along? In a January poll of some 400 people working in many different firms where the practices known as Agile and Scrum are being implemented, 88% reported tension between the way Agile/Scrum teams are managed in their organization and the way the rest of the organization is managed. Only 8% reported “no tension.”

Two different worlds

The reality is that “management” and “Agile” are two different worlds.

The world of “management” is vertical. Its natural habitat comprises tall buildings in places like New York. Its mindset is also vertical. “Strategy gets set at the top,” as Gary Hamel often explains. “Power trickles down. Big leaders appoint little leaders. Individuals compete for promotion. Compensation correlates with rank. Tasks are assigned. Managers assess performance. Rules tightly circumscribe discretion.” The purpose of this vertical world is self-evident: to make money for the shareholders, including the top executives. Its communications are top-down. Its values are efficiency and predictability. The key to succeeding in this world is tight control. Its dynamic is conservative: to preserve the gains of the past. Its workforce is dispirited. It has a hard time with innovation. Its companies are being systemically disrupted. Its economy — the Traditional Economy — is in decline.

The Agile world is horizontal. Its natural habitat is in low flat buildings in places like California, although it also spreading rapidly like a virus and has already established footholds in most of the tall vertical organizations. The Agile mindset is horizontal. Its purpose is to delight customers. Making money is the result, not the goal of its activities. Its focus is on continuous innovation. Its dynamic is enablement, rather than control. Its communications tend to be horizontal conversations. It aspires to liberate the full talents and capacities of those doing the work. It is oriented to understanding and creating the future. It believes in banking, not necessarily banks. It believes in accommodation, not necessarily hotels. It believes in transport, not necessarily cars. It believes in health, not necessarily hospitals. It believes in education, not necessarily schools. Its economy — the Creative Economy — is thriving.

The adults in the room?

The vertical world of management likes to position itself as “the adults in the room.” The following from an interview with Sam Palmisano, former CEO of IBM, in June 2014 in HBR is typical:

“You’ve got companies in great runs right now, the Googles and the Facebooks. Good ideas, great returns, but then all of a sudden, you need an act two. Well, jeez, is Act Two going to propel you from $30 billion to $100 billion? That’s a little tougher. It’s the Microsoft challenge.

“So you have to say, ‘Well, I need a different view. I can still create shareholder value, but I can do it a different way. I can rethink capital allocation.’ Recognize where you are on your maturity curve, as a management team, and behave accordingly. Don’t give a speech as CEO as if you just got out of Stanford and you came up with an iconic interface and you called yourself a piece of fruit.

Sadly, the real world is the opposite of the imaginary world that Palmisano inhabits.

The firms with “names like pieces of fruit” are not “$30 billion firms.” In fact, some of them are now much larger than the old 20th Century “giants.” Apple for instance is now more than four times the size of IBM.

Market capitalization

- Apple – $660 billion

- Google – $362 billion

- Facebook – $222 billion

- IBM – $155 billion

- GM – $54 billion

Whereas firms with a vertical mindset at the top, like IBM, are struggling with declining revenues and bloody cost-cutting reorganizations, firms in the horizontal world of Agile, like Apple and Google, are busy growing and inventing the future. Their second, third and fourth acts are already well under way.

What then is Agile?

For those managers who don’t know what the Agile is (itself a part of the problem), the horizontal world of Agile involves self-organizing teams that work in an iterative fashion and deliver continuous additional value directly to customers.

The practices of Agile that includes names like Scrum, XP, Kanban, DevOps and Continuous Development, grew out of lean manufacturing in Japan in the late 20th Century. As Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka wrote in “The New New Product Development Game” in HBR in January 1986:

This new emphasis on speed and flexibility calls for a different approach for managing new product development. The traditional sequential or “relay race” approach to product development… may conflict with the goals of maximum speed and flexibility. Instead, a holistic or “rugby” approach—where a team tries to go the distance as a unit, passing the ball back and forth—may better serve today’s competitive requirements.

In due course, Agile became a major force in software development, following the Agile Manifesto in 2001. More recently, it has been spreading to all sectors of the economy, not only in digital natives like Apple and Google, but also in significant pockets within large traditional organizations.

Agile was a response to hierarchical bureaucracy

Agile, Scrum and Lean arose as a deliberate response to the problems of hierarchical bureaucracy that is still pervasive in organizations today: falling rates of return on assets and on invested capital, a dispirited workforce, a decline in competitiveness and widespread disruption of existing business models.

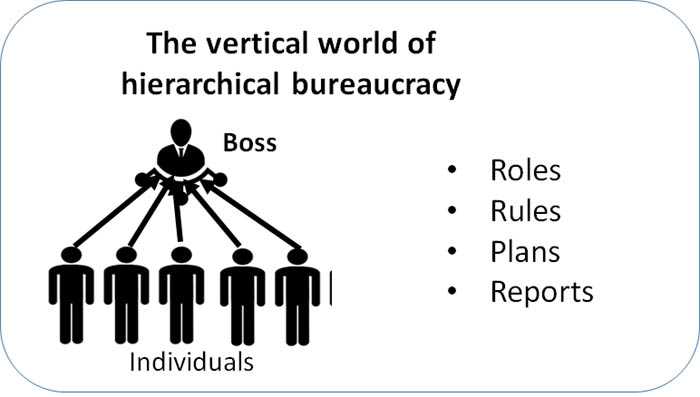

Given these problems, it’s easy to forget that hierarchical bureaucracy was a great advance when it was introduced over a hundred and fifty years ago. The basic idea of hierarchical bureaucracy is that work is organized with individuals reporting to bosses who tell them what to do and control their work. The roles, the rules, the plans, and the reports of hierarchical bureaucracy created order where previously there had been chaos.

As Gary Hamel has noted, hierarchical bureaucracy solved two essential problems:

- getting semiskilled employees to perform repetitive activities competently and efficiently;

- coordinating those efforts so that products could be produced in large quantities.

In a stable environment, it had great strengths. It was scalable. It was efficient. It was predictable and it delivered reliable average performance.

It had some liabilities. It was vertical. It was non-collaborative. Its plans were linear. It couldn’t change direction very fast. It was dispiriting to staff but at least people had a job. And the customer was noticeable by being totally absent: the focus was internal.

In a stable environment, these liabilities didn’t matter much.

Change wasn’t important. A firm could go on, grinding out the same basic product for years without much risk of harm. In a stable context, it could predict what customers would buy. It didn’t need to worry about customers. They could be manipulated by advertising.

With semi-skilled employees performing repetitive tasks, collaboration wasn’t important. And who really cared if the workers were dispirited? It was enough that they had their job and their paycheck.

In a world where workers were only semi-skilled and information was hard to come by, it made sense to put the boss in charge. In that setting, managers generally did know best.

Then the world became turbulent

But the world changed and the marketplace became turbulent. There were a number of factors: Globalization, deregulation, and new technology, particularly the Internet. The Internet changed everything:

- Power in the marketplace shifted from seller to buyer. Suddenly the customer was central, not something you could take for granted.

- Now the new norm as “better, cheaper, faster, smaller, more personalized and more convenient.” Average performance wasn’t good enough. Continuous innovation became a requirement.

- In a world that required continuous innovation, a dispirited workforce was a serious productivity problem.

- As the market shifted in ways that were difficult to predict, static plans became liabilities.

- The inability to adapt led to “big bang disruption.”

In this turbulent context, the strengths of hierarchical bureaucracy evaporated.

- Scalability turned into unmanageable complexity.

- The efficiency of economies of scale turned into diseconomies and inefficiency.

- Predictability turned into a crippling lack of agility.

- And reliable average performance wasn’t good enough for customers who wanted “faster, better, cheaper, smaller, more personalized and more convenient.”

The horizontal world of Agile

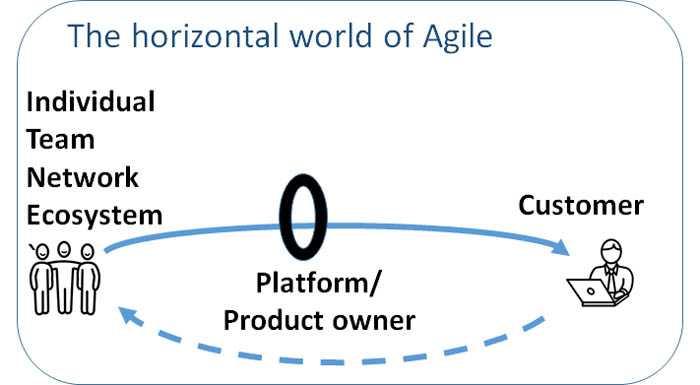

In the light of these problems, managers began to fundamentally rethink the way organizations are run. And so Agile was born. Scrum was notable among the approaches, but not the only one. The approaches all had certain features in common:

- Work is done by self-organizing teams that could mobilize the full talents of those doing the work.

- Work is focused directly on meeting customers’ needs.

- A “lens” focuses attention on the customers’ needs (when the lens is a person, as in Scrum, the person is known as a “product owner”; in large scale applications, the lens is “a platform.”)

- Work proceeds in an iterative fashion so that it can progressively satisfy customers’ needs better.

The arrangement can be pictured thus.

In this way of organizing work, the basic dynamics of the traditional economy are reversed.

Instead of a vertical dynamic of hierarchical bureaucracy with people reporting upwards to bosses, the firm was operating horizontally with a focus on the customer.

Instead of a controlling ideology, the approach is one of enabling self-organization.

Instead of static linear plans, plans are iterative and continuously on the move.

Instead of a workplace that is dispiriting to staff, the workplace is interesting, even inspiring, because people have the autonomy to deliver their best.

Instead of the customer being absent, the customer is now central. The goal of the firm is to delight the customer.

Copyright © 2015 Steve Denning

This article first appeared on Forbes.com in January 2015 and is republished here with the author’s permission.

![[Case Study] Lessons from descaling 25 Scrum teams](https://www.agilealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/descaling-teams-1200x630-1-150x150.jpg)

![[Case Study] Lessons from descaling 25 Scrum teams](https://www.agilealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/descaling-teams-1200x630-1-300x158.jpg)